Getting Started with Value Chains

May 30, 2020 · 6 min · Business

It's generally a good idea to understand how things work together. It doesn't matter if you're programming, practicing martial arts, or baking delicious bread. Frameworks are useful tools. In the case of business strategy, value chains are the poster child of frameworks.

I recently read some material from Nathan Baschez and Ben Thompson on the subject. This compiles everything I learned and aims to get you from zero to one as quickly as possible.

Defining Value Chains

When Michael Porter wrote Competitive Advantage, the business world was more focused on operational efficiency than strategy. Porter showed us that strategic thinking around what you do was more important in the long run than how you do it. In explaining this phenomenon, the concept of "the value chain" was born. Porter elaborates on this in his introduction:

At this book’s core is an activity-based theory of the firm. To compete in any industry, companies must perform a wide array of discrete activities such as processing orders, calling on customers, assembling products, and training employees. Activities, narrower than traditional functions such as marketing or R&D, are what generate cost and create value for buyers; they are the basic units of competitive advantage.

Competitive advantage comes from the activities that your business participates in rather than how well you do each one. The term "activity" can be a tough one to wrap your head around. In practice, activities can be any number of things that you choose to define. They are simply units to work with. You can be as specific or vague as you please.

One important thing to remember when picking out activities is that they should tie together into a cohesive narrative. Value chain analysis is just as much about how activities interact with each other as the activities themselves. Think of it as a chain of interlocking parts that work together to transform raw resources into completed products.

At his point in my learning process, I found myself nodding along to the effect of "I get it, just show me." I hear you. Let's take purchasing a new car for example:

You start with the design and prototyping. Then the car has to be manufactured. It gets distributed to sellers who find and convince willing consumers. Once a consumer buys a car, it has to get to them somehow. Finally, there is some customer support stuff that has to be addressed. This is simplified, but you get the idea. If you go granular enough, just about every problem to be solved has something unique about its value chain.

Execution is still front and center, but it makes sense that larger strategic gains come from activity manipulation. When you're focused on execution, everyone is working in a similar problem space. There's marginal upside to exploit.

On the other hand, value chain thinking can define and unlock completely new problem spaces with much more potential for growth. This is closely related to Blue Ocean Strategy, another popular framework to look into.

The Conservation of Modularity

At every step in the value chain, businesses are trying to make as much money as possible. This isn't super controversial. But more interestingly, why do some companies make more money than others? This is what Clay Christensen's Conservation of Modularity aims to explain.

There's more nuance to this theory than I'll give it credit for, but it comes down to the user experience. Christensen realized that the power (and profits) reside in the part of the value chain where you can improve the user experience the most. From a product perspective, this checks out. Great products solve real problems.

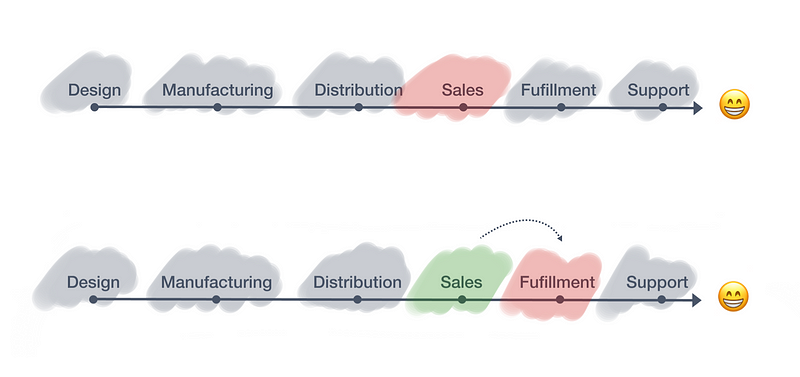

Here's the kicker: In order to improve the lacking parts of the user experience, you need control over the parts of the value chain where the problems are. Let's say the worst part of the car purchasing experience is closing out the sales process. If you happen to be Ford or Toyota, you don't have control over that part of the value chain. In that case, dealerships have the power. But of course, things can change.

When the most important problem in the value chain shifts, so does the power. In our cars example, someone might create a new seamless sales process that is way easier. Now the value chain reacts. The power moves to the new worst part of the user experience. Maybe it moves to fulfillment of purchased cars. When you have the power, you dictate the terms.

One thing we haven't covered yet is how to improve the user experience. Christensen thinks about this in an interesting way: Improving any system can be simplified to making components work better together. In our case, the system is the value chain and the components are the different activities.

So in order to gain power, you want to control the parts of the value chain where performance is not good enough and then integrate them in ways that improve things. Ironically, the next step is to hope that performance stays not good enough for a while, despite your improvements.

Product-Value Chain Fit

It's interesting to watch value chain strategy play out among the big dogs. Time and time again, large companies try to take on new markets and fail. When this happens, it's usually not an innovation or aptitude problem. Rather, it's all about the value chain. Ben Thompson unpacks this idea in The Value Chain Constraint, another Stratechery classic:

In this view, Amazon’s purchase of Whole Foods was an attempt to acquire a first best customer for its grocery delivery operation, one that would efficiently store and sell perishable goods that weren’t suitable for Amazon’s traditional e-commerce model. And, to be clear, this strategy may yet succeed, but only to the extent Amazon builds a completely new set of capabilities and integrations that will probably end up looking a lot like Walmart, which has a massive head start it is clearly taking advantage of.

In other words, what matters is not technological innovation. What matters is value chains and the point of integration on which a company’s sustainable differentiation is built; stray too far and even the most fearsome companies fall short.

Execution will only get you as far as the value chain allows. It's not necessarily about being "better" unless you have product-value chain fit. This is largely why you see companies like Microsoft traditionally deliver "feature-rich but poor UX" products in the consumer market. Their business was built on the enterprise value chain, where different attributes matter.

One common counterexample to this argument are companies like Netflix. At a glance, it looks like they had this huge pivot and jumped into a new market where technical excellence took them to the top. This isn't totally right, because the value chain remained largely the same. It's better to change the technology and keep the same value chain than it is to keep the technology and change the value chain.

It's not about technical excellence, it's all about integrations in specific value chains that produce positive feedback loops and outsized profits.

Next Steps

Once you have a solid understanding of all this stuff, you can apply it to your work! Force yourself to think through all the different activities that interact with your business. Map it out in some visual form. This might not be something you revisit every day, but the mental exercise of creating it will stick with you regardless.

Mapping out your value chain helps with a number of things:

- Awareness of tradeoffs in how we allocate our resources

- Identifying where you must be the best vs. just good enough

- Comparison against the competitive landscape

Your map informs what your company needs to do to be successful both today and further down the road. It can help in all sorts of ways from developing new products to spotting existential risks to predicting new entrants. This is a very subjective exercise, so try not to get bogged down in the details. Keep it as complicated or high-level as you want.

For more reading on how this looks in practice, the best thing to do is go to the source and start reading some of Clay Christensen's material. For those with a shorter attention span, the two newsletters that inspired this post (Divinations and Stratechery) are both good starting places.

As I go through this exercise myself, maybe I'll have more to share on our value chain at Hugo. Stay tuned and happy value-chaining!

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post and you’re feeling generous, perhaps like or retweet the thread on Twitter. You can also subscribe in the form below to get future posts like this one straight to your inbox. 🔥